By Indradyumna Swami

| January 12 – 20, 2005 |

Is my flight made its descent towards Colombo, the capitol of Sri Lanka, I gazed out at the tropical scenery below. Sri Lanka looked much the exotic land described in the in-flight magazine. It seemed all the more so when, after landing, I drove into the city with the local ISKCON temple president, Mahakarta das. The humidity, the endless array of rich green foliage, the luxuriant swirls of the Sinhalese alphabet, the multi-colored Buddhist flags and the variety of fruits on sale all made for what seemed a paradise. Indeed, Marco Polo described Sri Lanka as the finest island of its size in the world.

But like anywhere in the material world, Sri Lanka also has had its fair share of misery, which recent events have only confirmed. Just two weeks before I had arrived, a tsunami, a 10m wall of water created by an undersea earthquake thousands of miles away, ravaged much of the country’s beautiful 1,340km coastline.

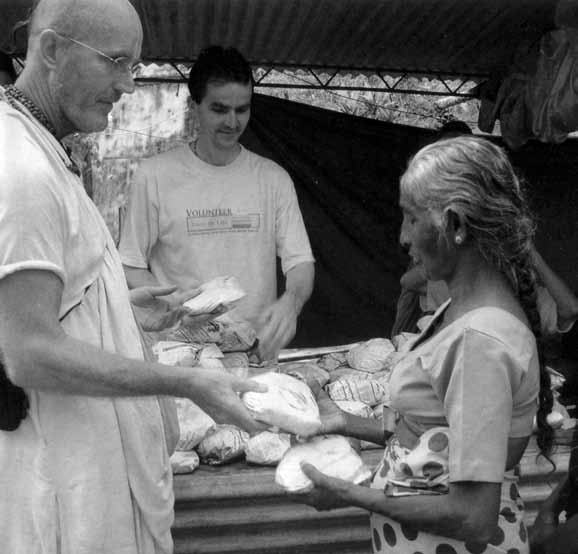

I had come to assist local devotees in the relief effort, not to enjoy the beauty of the island, which attracts an annual 400,000 tourists. As we stepped out of the car and into our small temple in the center of the city, Mahakarta said, “Since the tsunami hit we have been distributing prasadam in several towns along the coast. But it’s presently beyond our capacity to reach out effectively to the many victims of the catastrophe.”

“How many people have been affected?” I inquired.

“More than 33,000 have died,” Mahakarta replied, “and 835,000 have been made homeless, mainly in the southern and eastern coastal regions. The United Nations and numerous humanitarian organiza- tions are working to give food, shelter and badly needed supplies in these districts, but relations between the Sinhalese government and the Tamil Tiger rebels is hampering aid distribution to some areas.” Researching Sri Lanka before arriving, I had an idea of the po- litical situation. For more than 30 years the country has been em- broiled in a civil war between the minority (18%) Tamils in the north and the majority (74%) Sinhalese in the south. More than 60,000 people had died until a ceasefire was agreed in 2002. The fragile truce has been threatened, however, due to Tamil disatisfaction with alleged inaction over their demands for autonomy.

The tension evaporated with the tsunami. Although bickering broke out when the government was accused of giving more foreign aid to the Sinhalese, both sides are now preoccupied with burying their dead and caring for the survivors.

“We have to increase our prasadam distribution,” Mahakarta said. “Donors are sending a lot of funds.”

I agreed, but I was at a loss how to begin. Many relief orga- nizations were already at work and the government had recently complained that some of the smaller groups were actually getting in the way. As destroyed roads were repaired and washed-out bridges rebuilt, tons of supplies were being shipped into the affected areas. Army personnel and doctors from around the world were setting up camps along the coast to help victims. Those that survived the trag- edy were temporarily being moved into schools, sports stadiums, government buildings, or tents. Plans were already under way for the reconstruction of villages. But a law was quickly passed that no structures could be built within 500m of the shoreline—a precau- tion against future tsunamis.

It wouldn’t be easy to just jump into such a professional, well coordinated operation. It couldn’t be the usual American Food for Life program of driving to a downtown area and feeding the home- less. In Sri Lanka we would be working in a disaster zone.

I phoned Priyavrata dasa, director of Food for Life Global in America. Together we came up with the idea of calling the Red Cross and offering our help. It seemed wise to join in already-successful ef- forts. I could understand that we weren’t the first to offer help when the Red Cross secretary on the phone asked, “What particular con- tribution does your organization have to offer, Sir?”

I had to think quickly. “We’re prepared to cook and distribute hot meals, Ma’am.”

There was a short pause, then the secretary said, “Give me your number and I’ll call you back in an hour.”

Forty-five minutes later my cell-phone rang and the secretary said, “I have made an appointment for you with the president’s sec- retary at 4pm today.”

“The presidential secretary of the Red Cross?” I queried. “No, Sir, with the secretary of the President of Sri Lanka.”

“Oh, yes, of course,” I replied, trying to hold back my excite- ment.

That afternoon, accompanied by Mahakarta das, I met the president’s secretary, Mr Krishnan. Needless to say, he was a little surprised when we entered his office in our robes.

Standing up and shaking my hand, he said, “I am in charge of organizing the present relief work in our country. I am dealing with the main disaster relief organizations, such as Oxfam, Care, Red Cross, Medicine sans Frontier, UNICEF, etc.”

Squinting at me, he said, “Which organization do you repre- sent?”

“Food for Life—Global,” I replied. “A branch of the Interna- tional Society for Krsna consciousness.”

“Food for Life—Global?” he said.

Again I had to think quickly. Seeing a computer on his desk, I said, “Yes, Sir. Please look at our website: www.FFL.org.”

He typed in the address, and when the website came up he studied it carefully.

“I see,” he said after a few minutes. “Very impressive. So your people can distribute hot meals to the victims of the tsunami?”

“Yes, Sir. We’re experienced in the matter. It’s vegetarian food— no meat, fish or eggs. Will people be inclined to eat that? I heard most of the tsunami victims were fishermen.”

“For now it’s not a problem,” he replied. “At the moment, the fisherman are not eating fish because they say the fish are eating the dead bodies of their relatives washed out to sea by the tsunami.”

“Oh, I see,” I said grimmacing.

“How many can you feed daily?” he asked.

“Five thousand to begin with,” I replied. “And more later.”

He picked up the phone and dialed a number. My eyebrows went up as he began to speak.

“Major-General Kulatuga? This is the presidential secretary. I understand you need help with food relief in the Matara district. I have a group of people here who can cook and distribute food for 5,000 people a day. They can increase that number as the weeks go by. Are you interested?”

The reply must have been immediate, for Mr Krishnan said, “Yes, Sir, I’ll send them down immediately to discuss the details with you.”

Foreseeing that any relief work we would do in Sri Lanka would be a major operation, I had requested several devotees from my Polish festival tour to join me. Tara das and his fiancee, Radha Sakhi Vrnda dasi, flew from Greece where they were distributing books, Santi Pa- rayana das and Rasamayi dasi came from Mayapura, Niti laksa das from London, and Laksminath das (who runs Food for Life in Dur- ban, South Africa) also made the journey. Dwijapriya dasi and her two sons, Dhruva and Devala, joined us from America. With several of the men, we set out the next day in a van along the coastal road south towards the district of Matara, one of the worst affected areas.

The mood in the car was upbeat. Within 24 hours of arriving in the country we had met the president’s secretary, who had given us government authorization to distribute food in a designated area, and we were about to meet the military to discuss the logistics of distributing food to refugees. The mood switched from upbeat to light when a devotee mentioned the bad weather in Europe and how we were in the tropics. But we were soon reminded that this material world is a fool’s paradise at best.

Forty-five minutes into our journey we rounded a bend on the winding coast road. Suddenly all of us became silent. An entire vil- lage had been reduced to rubble. As our driver instinctively slowed down, we saw the destructive power of a tsunami. Not a house in the village was left standing, the entire place a pile of broken con- crete, twisted steel, and splinters of glass and wood.

“My dear Lord!” one devotee exclaimed.

“I can’t believe what I am seeing!” said another.

The worst thing I had ever seen was the destruction in Sarajevo, Bosnia, just after the end of the Balkan War. I thought I would never witness anything more terrible. An entire city had been ravaged. But as we drove through more villages and towns leveled by the tsunami, I realized it was unprecedented in recent history: 33,000 people had been killed in just under 30 seconds. That’s how long it took the 10m wave, moving rapidly as it hit the shoreline, to devastate the villages. Witnessing it first hand certainly had a more pronounced effect on me than seeing it in the media.

As we continued driving my heart broke seeing people, 20 days after the tragedy, sitting dazed in the ruins of what used to be their homes or businesses. Some were crying. We passed one home that was partially standing. The facade of the house had been ripped away revealing several bedrooms. Inexplicably, despite the force of the tsunami, children’s clothes were neatly folded on shelves in one room.

ruins of what used to be their homes.

Mesmerized, I hadn’t even taken my camera out to take pic- tures for an article I had been asked to write for Back to Godhead magazine. Grabbing the camera, I now clicked away kilometer after kilometer, trying to capture the destruction. Suddenly, I stopped the photographic frenzy and put the camera away. “There’s no hurry, “ I thought. “You’ll be seeing scenes like this every day for the next month.”

Every 2-3km I noticed fresh graves alongside the road. “There was no time to transport the bodies elsewhere,” said our driver. “All of these roads were closed because of debris.”

In some places we passed lines of survivors standing by the road.

I inquired from our driver what they were doing.

“They’ve lost everything,” he said. “They’re standing there hop- ing people will stop and give them anything—cooking utensils, clothes, toys, some comforting words.”

Although Krsna says in Bhagavad-gita that a devotee does not lament for the living or the dead, at that moment I felt genuine saddness for those people. Unable to offer any practical assistance, I prayed to Srila Prabhupada that they would have the opportunity for devotional service, the panacea for all suffering in this material world.

Struggle for existence A Human race,

The only hope His Divine Grace.

[ From Srila Prabhupada’s Vyasa-puja offering, 1932 ]

After three hours of driving past crumbled homes, smashed cars, upturned boats and piles of rubble with untold pieces of household paraphernalia, I couldn’t watch any longer. I took out my Bhagavad- gita and began to read. I thought, “From this day on, if you enter- tain even the slightest desire to enjoy this world you’re simply a fool and the greatest hypocrite.”

While passing through one village, our driver said, “In this town 11,000 people died and 230 cars were washed out to sea.”

I looked up briefly to see a little girl crying next to her mother on the steps of what must have been their home. I also noticed that the traffic was moving slowly. There was none of the usual speeding and passing cars, the sound of engines roaring and the continuous honking that one generally experiences on Asian roads. Seemingly out of respect for the tsunami victims—living and dead—the traffic moved at a funereal pace.

A slight respite came sometime later, just before we turned off the road towards the army camp. Looking up from my reading, I saw a large black dog sitting in the ruins of a decimated house. I had noticed very few animals along the coast. Obviously some had been swept away, while many seemed to have instinctively anticipated the tsunami and run in search of shelter. Somehow this dog had survived and looked quite well. I asked the driver to slow down and I called out “Hare Krsna!” to the animal. He heard me and ran ex- citedly towards the car. I waved as we passed him. A moment later I looked back and saw him sitting by the road wagging his tail—eyes still fixed on our car.

Somehow our little exchange in the midst of all the sorrow had encouraged us both. “In the worst of times,” I thought, “a little love goes a long way.”

A few minutes later we pulled into the army camp. The sergeant- at-arms was waiting for us and quickly escorted us into a room with a large oval table surrounded by 12 chairs. A few minutes later Ma- jor-General Kulatuga entered, accompanied by six of his staff. Like Mr Krishnan the day before, he looked surprised to see our robes. As we stood to greet him, I shook his hand and remained standing until he was seated.

The mood was formal as the Major-General began his briefing. Standing with stick in hand, he pointed to the wall full of maps and charts.

“Here in Matara district there are 1,342 confirmed deaths, 8,288 people injured, 613 missing and 7,390 families have lost their homes and are living in camps for displaced persons.”

Turning around and looking at me, he said, “We prefer not to call them refugee camps.” Then, with emotion in his voice, he con- tinued, “They are our people, not refugees. Do you understand?”

With scenes of people sitting hopelessly in their devastated homes still fresh in my mind, I replied, “Yes, Sir. I do understand.”

Still looking at me, he emphasised the need of the hour. “We are professional soldiers. We fought the Tamil Tigers for years. But now we are busy clearing the roads of debris, cleaning wells and repairing buildings.”

“And we are here to help you,” I said.

Pausing, and with less formality, he said, “Thank you.”

Turning back to the maps and charts, he said, “Our priorities are reopening the hospitals and schools, rebuilding the bridges, and restoring communication. Seventy-five percent of all telecommuni- cation, 80% of all contaminated water supplies, and 87% of elec- tricity have been restored.”

Looking at me again, he said, “Your contribution will be to feed the people in camps for displaced persons. Mr Krishnan told me you can provide hot meals. Is that correct?

“Affirmative, Sir.”

Pausing again, he looked at me curiously and said, “You were a military man?”

“Yes, Sir,” I said with emphasis, as a soldier does when address- ing a superior officer.

Smiling, he nodded his head, obviously more comfortable with our cooperation.

“Now you will visit one of the camps so you can get an idea of what is happening.” Turning to one of his staff he said, “Major Janaka, take them to Rahula College. I believe we have over a thou- sand displaced persons there.”

Following in our van behind the Major and six armed soldiers in a truck, we drove for 30 minutes to the camp for displaced per- sons. Getting out of our vehicles, we walked into the camp and were immediately the object of everyone’s attention. Due to the humid- ity, only the children were active. Most adults sat about talking in small groups. I noticed a huge pile of clothes on the campus lawn, obviously donations, through which several women were rummag- ing. There was an improvised medical clinic in one classroom, where three members of the Red Cross were attending to a few infants. Five army soldiers, obviously present at the camp for security, sat casually nearby.

It was a sober scene. Though the horror of the devastation was kilometers away on the beachfront, the reality that these people had lost family members, homes and professions was close at hand in the looks on their faces. When I smiled at one elderly couple sitting on the lawn, they stared back at me with no emotion. I saw many such people. Others expressed their loss when I spoke with them. The Major told me that most people in the camp had lost one or more relatives—and everyone had lost their home. Once again the magnitude of the tragedy hit me.

“You can cook over here,” the Major said, pointing to a nearby shed. As we approached the site, I noticed a number of people cook- ing rice and subjis.

“Where are they getting their foodstuffs to cook?” I inquired from the Major.

“We are providing them,” he replied.

I was a little surprised. “Is that the case with all the camps in this area?” I asked.

“Yes, it is.”

“And throughout the country?” I inquired further. “For the most part.”

I was taken aback. The media in the West had given the impres- sion that victims of the tsunami were in desperate need of food.

“I thought people here were hungry, Major.”

“They were in the initial stages of the disaster—for the first week,” he replied, “but we have things under control now. The world has given us ample food, medicine and other supplies.”

“Then what part do we have to play?” I asked.

“You can take some of the burden. My men are overworked delivering supplies to the 35 camps in this region. We’ve been here for three weeks. All relief organizations have a part to play and every effort helps in serving the people who survived the tsunami.”

As I reflected on his words, he stepped closer and said, “The government will be grateful for anything you can do, I assure you.”

I looked around and surveyed the camp again. “It’s no small thing if the government acknowledges our support in relief work at this difficult time,” I thought. “It will surely bear fruit in the future. And, what’s more, we’ll be distributing prasadam, the mercy of the Lord. Such mercy is the best of all forms of welfare.”

Breaking my meditation, I shook his hand and said, “We’ll play our part. We’ll begin in three days.”

Quickly jumping into our van, we headed back to Colombo to pick up the rest of the team and supplies. Making a quick calcula- tion, I realised we’d require tons of rice, dhal and vegetables. I called Mr Krishnan and requested a large truck to carry the goods south. He replied it was ready anytime.

As we journeyed, I watched again in disbelief at the destruction. At one point we ran into a huge traffic jam. As we waited, our driver pointed to an empty battered train with 15 coaches, standing still on the railway line just 30m away.

“That train was hit broadside by the tsunami,” he said. “Over 1,000 people died. No one survived. They are still finding bodies in the area.”

As I looked closer I could see men with white masks around their mouths and noses, digging in the mud nearby.

“The masks are for the stench of death,” the driver said. “It’s been almost three weeks and any corpses remaining are very deteriorated.” It was yet another stark reminder of the cruel face of material nature. I turned my eyes from the scene. I’d had enough for one day.

Enough tales of death. Enough scenes of descruction. Enough of the tsunami.

“Move on!” I shouted at the driver as the traffic cleared. He looked back at me.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “It’s been a difficult day.”

As he accelerated, I thought, “Tomorrow will bring relief, for we’ll begin distributing prasadam.”

But just 2km down the road we witnessed yet another reminder of material existence: the aftermath of a head-on collision between two cars.

“Don’t look,” one devotee said turning from the scene.

“Don’t worry, I won’t,” I replied as I closed my eyes and started to chant japa. “When will it end?” I thought.

It must have been only two minutes later that Krsna showed me the final and most painful lesson of the day. We rounded a bend and suddenly a dog ran into our path, pausing just in front of our car. I immediately recognized it as the dog I had waved to earlier in the day.

“Watch out!” I yelled.

But the poor creature never had a chance. Just as he turned his face towards us, our van ploughed into him with a loud thud. Dis- appearing under the vehicle, I heard his body being crushed under the wheels. The driver had failed to slow down.

It was dusk, so no one saw the tear that glided down my face and dropped silently onto the floor of the van. But I guessed they could sense I was affected.

“It was just a dog,” the driver said.

“He was more than that, “ I said softly. “He was a spark of life among all the death and destruction I saw today.”

“The day’s almost over, Maharaja,” one devotee said. “We’ll be home soon.”

“Yes,” I said under my breath, “I want to go home, to the spiri- tual world, and never return to this world of birth and death.”

etam sa asthaya paratma nistham

adhyasitam purvatamair maharsibhih

aham tarisyami duranta param

tamo mukundanghri nisevayaiva

I shall cross over the insurmountable ocean of nescience by being firmly fixed in the service of the lotus feet of Krsna. This was approved by the previous acaryas, who were fixed in firm devotion to the Lord, Paramatma, the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

[Srimad-Bhagavatam 11.23. 57—One of the sannyasa mantras given by the guru at the moment of initiation into the renounced order of life.]