By Indradyumna Swami

| December 25, 2004 – January 11, 2005 |

Like most people, in the early hours of December 26, 2004, I had no idea what the word tsunami meant. Had I been a tourist on the beach at Phuket, Thailand, sunbathing on that

ill-fated day the “harbor wave” (the Japanese translation for tsuna- mi) hit, I probably would not have taken heed when a vacationing scientist, seeing the sea mysterious-

ly recede several hundred meters, screamed out a warning to others, “” ” and ran for his life. He survived, but most on the beach didn’t.

The death toll the deadly wave caused in 12 countries around the Indian Ocean may never be known, but it is estimated that more than 200,000 people lost their lives, with many thousands missing. 500,000 were injured and millions left homeless.

I had just arrived in Australia to participate in the Sydney tem- ple’s Christmas marathon festival. The day after Christmas we were returning from a joyous harinam on Sydney’s packed streets when I saw the word tsunami in the headlines in the evening newspa- pers. “Huge waves devastate populated areas in the Indian Ocean!” screamed one.

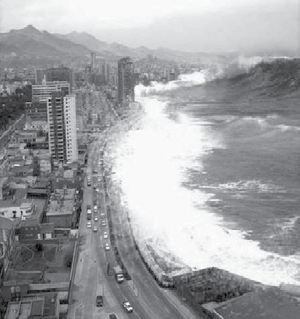

Within hours the world was educated in the deadly phenom- enon of a tsunami. The event was caused by a powerful underwater earthquake near Indonesia. The energy released by the quake was equivalent to 40,000 “little boys”—the atom bomb detonated over Hiroshima. It was equal to a billion bolts of lightning. The explosion was so strong that studies show the earth might have wobbled on its axis by as much as an inch and the length of the day altered by microseconds. So forceful as the earthquake that islands southwest of Sumatra (closest to the epicenter) moved by more than 20m.

The quake created 10m waves that fanned out and moved at speeds of up to 750kph across the ocean, eventually slamming into populated areas.

The rest is history, as the media was soon saturated with news of the destruction the waves caused.

Like millions around the world, I sat in disbelief as I read the news reports. Within hours rescue work began in all the countries affected, including Indonesia, Thailand, India and Sri Lanka. An unprecedented out-pouring of sympathy from people around the world would eventually raise over 5 billion dollars for relief work.

A devotee of the Lord is not callous to such catastrophes. He doesn’t simply pass them off as global karma. By his very nature a devotee is sensitive to the suffering of others. Although Arjuna’s concern for his family members and their suffering is often analysed as a weakness, it has also been described as characteristic of a pure devotee:

Any man who has genuine devotion to the Lord has all the good qualities … as such, Arjuna, just after seeing his kins- men, friends and relatives on the battlefield, was at once over- whelmed by compassion for them who had so decided to fight amongst themselves … he was a crying out of compassion. Such symptoms in Arjuna were not due to weakness but to his softheartedness, a characteristic of a pure devotee of the Lord.

[Bhagavad-gita 1.28, purport]

The more the media revealed the suffering caused by the di- saster, the more I began thinking of helping in the relief work. Al- though I am usually busy with various responsibilities, ironically, at that moment I had the time. Just after the new year, I was planning to go to Durban, South Africa, for a month-long break.

But the past 12 months had been particularly intense, and I sorely needed time to recuperate my health. I also hankered for time to read and chant. I had planned to do so in Vrindavan during the month of Kartika, but had sacrificed the time to take my disciples on parikramas. After giving the matter much thought, I concluded that because of my physical exhaustion and need to spiritually re- plenish myself, I would go to Durban as planned.

On January 2, I arrived at Sydney airport to catch a flight to Mumbai, and on to Durban. While passing through the airport, I was bombarded with media coverage of the tragedy. Newspapers and magazines still carried front-page reports on the devastation. Televisions in lounges aired heart-breaking scenes of destruction and appeals for help.

I stopped briefly outside one cafe and joined a group of people watching a television newscaster describe how some remote areas and islands near Indonesia still had not been reached by relief work- ers two weeks after the tragedy. He said that entire indigenous tribes living in India’s Andaman and Nicobar islands may have perished. Smiling slightly, he described how a hail of arrows, fired from the forest of one tiny island at an Indian coastguard helicopter hovering above, suggested there were at least some survivors. But as I looked around at the crowd watching the report, not one person smiled. They found nothing humorous in the tragedy.

By the time I checked in for the flight, I was again in duality. “People are suffering in vast numbers,” I thought to myself. “The whole world seems to be reaching out to help them by offering welfare in one way or another. Surely devotees should be there as well, offering spiritual welfare in the form of prasadam and the holy names. I have time to help. Perhaps I actually should go.”

After checking in, I proceeded towards a security checkpoint near to my departure gate. As I put my bags on the conveyor belt to be x-rayed, a security official on the other side smiled at me. After I passed through a body check, he called me over and asked me to open one of my bags. As I stood there he said, “It a wonderful thing you’re doing.”

A little surprised, I replied, “Excuse me?”

“Going over there to help those people,” he said. “I know Hare Krsnas give out a lot of food here in Australia. But now it’s really needed in those places hit by the tsunami.”

“But I’m not actually “ I started to say.

“If I could go, I would,” he cut in, “but really it’s the work of people like you. It’s your business to help others.”

I stood there speechless.

“God will bless you,” he said, patting me on the back. I turned and walked towards my departure gate.

As the flight took off I looked out of the window. The security man’s words echoed in my mind. “It’s your business to help others.” “But it’s my break,” I said to myself. “I need rest,” and my thoughts drifted off to Durban and the warm summer weather, the pool where I’d be doing my laps every day, the extra rounds I’d be chanting and the books I’d be studying.

“I’m doing the right thing,” I thought. “After all, Krsna says in

Bhagavad-gita that a yogi is balanced in his work and recreation.

yuktahara viharasya

yukta cestasya karmasu

yukta svapnavabodhasya

yogo bhavati dukha ha

He who is regulated in his habits of eating, sleeping, recreation and work can mitigate all material pains by practicing the yoga system.

[Bhagavad-gita 6.17]

Only such a balanced program of study and preaching qualifies one to attain Vaikuntha, the spiritual world. If I was serious about achieving the perfection of life, I’d have to strike the balance.

Exhausted from the long festival in Sydney, I soon drifted off to sleep. It must have been an hour later that I heard someone address me.

“I’m sorry,” said the steward. “Did I wake you?” “No,” I replied. “It’s OK. I was just napping.” He sat down in the empty seat next to me.

“It’s people like you who will make a difference in the lives of those who are suffering from that horrible disaster,” he said.

My eyebrows went up as I looked at him in surprise.

“When I was younger I often went to your Crossroads center in Melbourne to eat,” he said. “I was pretty down and out at the time.

If it wasn’t for your food, I don’t know what would have happened to me. You must be going over to India to feed the victims of the tsunami. Or are you going to Sri Lanka?”

I hesitated to say anything. Taking my silence as an expression of humility, he put his hand on my shoulder.

“Thank you” he said. And then he got up and walked away.

The person across the aisle overheard his remarks and nodded his head at me, appreciating my supposed mission of mercy. Re- sponding, I slighted bowed my own head—in reality hiding my guilt at receiving such undeserving praise.

I turned and looked out of the window again. It was getting dark. “Is all this just a coincidence, or is Krsna trying to tell me something?” I thought to myself. Then while looking at my reflec- tion in the glass, I said softly to myself: “Putting the mystical aside, the writing is clearly on the wall. You’re off to one of the areas dev- astated by the tsunami.”

I took the in-flight magazine out of the seat pouch in front of me and scanned the world map at the back. Chennai, one of the ar- eas hit by the wave, was closest to Mumbai, where I would be spend- ing one day before heading to Durban. Upon landing in Mumbai, I sent an email to Bhanu Swami asking if he needed help with relief work. He wrote back quickly:

“For the moment we are doing prasadam distribution in Chen- nai where not so many lives were lost. Sri Lanka is bad and Sumatra is even worse.”

Sri Lanka was obviously closer, so I called the temple in Co- lombo and spoke with the temple president, Mahakarta prabhu.

“We’re not equipped to do any significant relief work at the mo- ment,” he said, “but we hope to build it up.”

My last chance was Indonesia. But by evening I had learned that Gaura Mandala Bhumi, the devotee in charge of ISKCON there, had sent out a communication that for the moment there was not much he and the other devotees could do, as the affected area was 2,000km away and difficult to access.

With no relief work in sight, the next day I boarded my flight to South Africa.

Arriving in Durban early in the morning, I quickly settled into my quarters at the temple. Placing all my books neatly on a shelf near my desk, I thought, “I’ll start with Caitanya-caritamrta and af- ter a few days I’ll begin the second volume of Brhat Bhagavatamrta.” While arranging my CDs in a drawer in the desk, I thought, “And I’ll listen to three lectures of Srila Prabhupada each day, and several of my godbrothers as well!”

At noon I gave instructions to the cooks: “I’d like simple healthy prasadam while I’m here. Lots of salads.”

And to my assistant, Anesh, I said, “Register me with the local gym. I’ll swim in the pool for two hours every day.”

By the evening I had made a schedule for myself, beginning with rising at 2am and going to bed by 8pm. “After six weeks I’ll be as fit as a fiddle,” I joked with Anesh.

“And well read, too,” he replied with a smile.

It was getting late and as I prepared to take rest, I said to Anesh, “Please download my mail before I go to sleep.”

As I dozed off I heard Anesh say, “You have four emails, Srila Gurudeva.”

“Who are they from?” I said half asleep.

“Well, the first one’s from Mahakarta das in Sri Lanka,” he said.

My eyes popped open and I jumped out of bed.

“I have been thinking about you since you spoke to me when I was at Trincomalee,” Mahakarta began. “We are doing prasadam dis- tribution successfully there as we have some local support to help us. “But during the past two days there have been many offers of help from devotees around the world who are willing to donate money and even volunteer for our relief work. Please, I am begging

you to come and help us coordinate everything.”

I sat for several moments in the chair, thinking to myself. “Gurudeva,” said Anesh. “It’s getting late. You should to go to bed.”

“Maybe Krsna actually is trying to tell me something,” I said softly to myself.

“What’s that?” said Anesh.

I looked up. “Book me a ticket to Sri Lanka as soon as you can,” I said.

He was dumbfounded. “Gurudeva! Book you to where? Sri Lanka? You just got here!” he said.

Throughout the next few days, I solicited donations from lo- cal devotees for the work ahead. They gave generously, like people around the world were doing.

As the devotees drove me to the airport for my flight on January 11, my heart beat in expectation of the mission ahead. An historic opportunity was at hand. Much of the world was aiding the suffering of the people affected by the tsunami. Billions of dollars of aid was pouring into the area. All the main humanitarian organizations were mobilizing and tons of food, medicine and clothing were on their way. ISKCON could hardly match such resources. But we had our part to play. As humble as our effort would be—a little prasad and some kirtan of the holy names—these things are of a spiritual na- ture, capable of delivering one beyond the world of birth and death. As I boarded the flight to Colombo I knew I had taken the right decision. A devotee is duty bound to put others’ interests before his own.

But what about my striking the balance of sadhana and preach- ing in order to go back to the spiritual world?

If the words of the security official at the Sydney airport proved true, I had nothing to worry about.

“It’s your business to help others,” he’d said. “God will bless you.”

The self-effulgent Vaikuntha planets, by whose illumination alone all the illuminating planets within this material world give off reflected light, cannot be reached by those who are not merciful to other living entities. Only persons who constantly engage in welfare activities for other living entities can reach the Vaikuntha planets.

[Srimad-Bhagavatam 4.12.36]