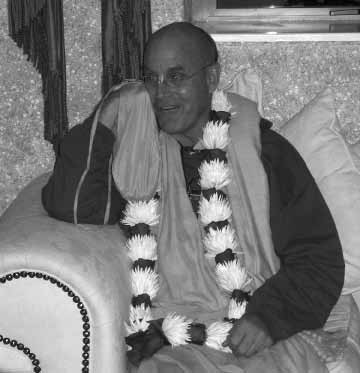

By Indradyumna Swami

| August 26 – September 8, 2006 |

After the Polish festival tour, I went to New Vraja Dhama in Hungary. Under the guidance of Sivarama Swami, it has become one of the most successful communities in ISKCON. I had planned to read and chant in the spiritual atmosphere there, but instead I found myself giving most of my time to my disciples, some of whom had even come from Croatia, Bosnia, and other neighboring countries to see me. And I, having been away from them for a year, was just as eager to see them.

Then I went to Ukraine and participated in the yearly one-week devotee festival in Odessa. Once again, every minute was spent teaching and counseling my disciples. I often ask my disciples how they joined the Krsna consciousness movement, and in Odessa I found the story of a mother and daughter, particularly interesting. It is often miraculous how fallen souls are reunited with the Lord and His devotees.

Kishori dasi, 91, was born into a poor but pious Russian family in 1915. In her youth, she was saw her grandfather, who had never been sick a day in his life, pass away at the age of 115 in a church while reciting the names of God.

“But why should we talk about my past life?” Kishori humbly protested. “It was only suffering and misery.”

“Sometimes it’s good to remember our past,” I said, “so we can appreciate our good fortune in the present.”

Reluctantly, she continued. “We lived in a small village in the Russian countryside,” she said. “I was the youngest of 11 children. My mother died when I was two, and my father struggled to maintain us by working in a factory. As soon as we children were capable, we worked in the fields. I remember hot summers harvesting hay and harsh winters huddling around the fireplace with my brothers and sisters in our wood cabin.

“We never had much time to play. Our only solace was going to church on Sundays. We’d walk 12 kilometers there and back. I always prayed to God to take me to heaven. I told him I wasn’t happy on earth.

“But things got worse before they got better. When I was 12 my father died, and we children became orphans. All of us had no choice but to stop school and go to work. It was either work or starve. I found work in the same factory my father had served in most of his life.

“Fortunately, a teacher in a local school took pity on me and tutored me in her spare time. Going to church and praying to God was all that made sense in life at that time, but as I grew older, I became dissatisfied with the sermons, as they didn’t explain enough about God. I was frustrated. ‘How will I ever know Him?’ I often said to my friends.

“Life in the village was always the same. The main activity of the men was getting drunk and fighting. I wanted to escape, but where could I go? Again I prayed to God for help.”

Kishori paused for a moment. “Guru Maharaja,” she said, “who will care to hear my story? Most Russians have a similar story: a hard struggle for existence.”

“I agree,” I said, “but I’m sure it will make the final chapter of your life all that more relishable. Please go on.”

She sighed. “Yes, Guru Maharaja,” she said. “My tutor taught me accounting, and when I was 18 I was able to get a good job at military base 100 kilometers away. I moved there, eventually met an officer, and married him.

“But our happiness was short-lived. World War Two started, and he was sent to the front. I was alone for four years. I was fortunate that at the end of the war he came home, although severely wounded. But at least he came back. Most of his fellow officers didn’t. I had to give solace to many widows.”

As Kishori was speaking a number of children came into my room to see me. Kishori turned to them. “Guru Maharaja is asking me to speak about my life,” she said. “But real life began when

I met the devotees of Krsna. Before that it was only one sad story after another. Take my advice and always take shelter of guru and Krsna. Never stray from the instructions they give you.”

The children just stared at her with blank faces.

“Before the war I had given birth to Thakurani dasi,” Kishori continued. “Of course, she wasn’t called Thakurani then. Neither of us could have ever imagined one day we’d be devotees of Lord Krsna. She was my only daughter, and as she grew up we became very close, especially after my husband died. Thakurani and I spent a lot of time at the church, but my frustration with finding answers to my deeper questions rubbed off on her.

“After she married, she was shocked when her husband, a staunch follower of the Communist Party, began denouncing God. She couldn’t bear it, and she eventually divorced him. We became despondent, caught between a religion unable to answer our soul-searching questions and a government steeped in atheism. We often prayed that God would lead us to the truth.

“In the early 1960s we became desperate to find a path that could explain everything about God and how to love Him. Having no one to guide us, we did the only thing possible at the time: we searched for knowledge in the public libraries. The Communist Party was proud of its large libraries educating people in all sorts of mundane knowledge, but because of the volume of literature, spiritual books also found their way onto the shelves.

“One day we stumbled across a copy of the Bhagavad-gita printed in the late 1800s. The library did not lend out books, so each day we would return and eagerly read the copy in the library. It seemed to answer all the questions we had about life, death, creation, God, and the spiritual world. We read with a passion.

“With further searching we came across an old copy of the Mahabharata. We spent all our spare time in the library reading it together. Finally, we decided we must have the books for ourselves, so for months we painstakingly copied them by hand. It took time because, as you know, the Mahabharata has thousands of verses. By copying them we also mastered them.

“But as a result, we encountered a new type of frustration. We learned that to realize the knowledge we had to serve a spiritual master. But where in Russia, deep behind the Iron Curtain at the height of Communism, would we find a guru? We became hopeless, but continued praying.

“Years went by. We found other scriptures from India in the libraries. They all reinforced our understanding that we needed personal guidance from a spiritual master. And we were getting older. By 1989 I was 74 and Thakurani was 51. There wasn’t much time left, but one day the Lord took compassion on us.

“It was in the spring of 1990, on the eve of the fall of Communism, when we were walking down a street in Odessa and a young man quietly approached us with a book under his arm, all the while looking around to be sure the police weren’t watching. We were startled when he put the Bhagavad-gita As It Is into our hands. We wanted so much to purchase it, but we didn’t have enough money.

“We took his address, worked hard at extra jobs for a few weeks, and after contacting him again, bought the Bhagavad-gita. We were thrilled when he told us there were a number of people meeting secretly to read and chant Hare Krsna together, for Communism was still in force and religious meetings were forbidden.

“We were happy to finally find people like us, interested in the culture and philosophy of India. But one thing was still missing: we didn’t have a spiritual master. Our prayers for mercy reached a feverish state.

“Finally the Lord heard us. Six months later the regime fell and you came to Odessa to give lectures on Bhagavad-gita. That’s when you accepted us as your aspiring disciples. The next year we were initiated.

“The Lord waited a long time to answer our fervent prayers. From my childhood I was always praying to him. I’d almost lost hope, and finally he rescued us.”

Kishori chuckled. “Guru Maharaja,” she said, “may I stop speaking about myself now and say some words in glorification of you?”

I laughed. “Let’s not spoil the story,” I said. “It may well go into my diary.”

Kishori nodded and smiled.

dinadau murare nisadau murare

dinardhe murare nisardhe murare

dinante murare nisante murare

tvam eko gatir nas tvam eko gatir nah

“O Lord Murari, during the beginning, middle, and end of all our days and nights, You always remain the only goal of our lives.”

[Sri Daksinatya, Srila Rupa Goswami’s Padyavali, Text 73]